I didn’t spend too much time in Osh, the second largest city in Kyrgyzstan. I took a short walk around the city to find a new pair of shorts after losing mine in Tajikistan. Procuring them in a Muslim country posed a challenge, but I eventually found some at the bustling market. Departing from Osh wasn’t easy. Although I was tempted to spend another night relaxing at the hostel, I knew I was just being lazy and had to press on and explore more of Kyrgyzstan.

Over the next day and a half, I made decent progress, but the cycling through towns on the outskirts of the city and vast farmlands wasn’t particularly inspiring. However, as I ventured into the mountains, the roads quickly deteriorated, and the feeling of being back in the wild engulfed me.

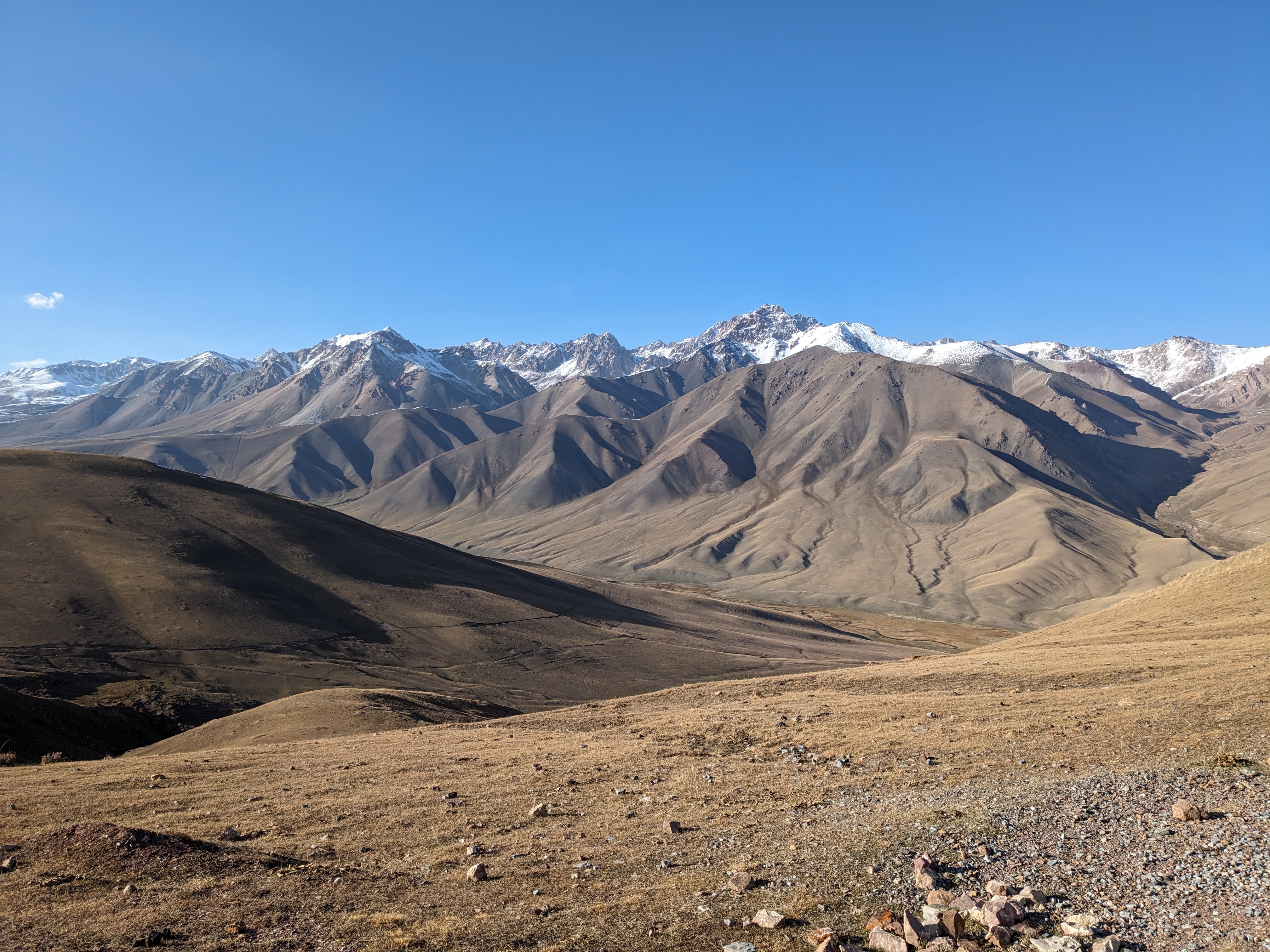

The first obstacle I encountered was a mountain pass exceeding 3000m. Kyrgyzstan’s wetter climate compared to Tajikistan meant snow capped many of the mountains. Scaling each pass, I never quite knew how much snow awaited me at the summit.

During the ascent, a massive flock of eagles (I think) soared above me, an awe-inspiring sight I shared with a local man riding his horse. The locals’ way of life fascinated me, with many living in yurts and tending to herds of animals. It felt like they were living the same way as their ancestors did 2000 years ago.

The view from the top was amazing and always made better by the feeling you earnt it by cycling there. Luckily, there wasn’t any snow covering the road, and I quickly descended down the other side to the warmer temperatures in the valley, making camp by a river for the night.

Numerous fellow cyclists had eagerly told me about the brand-new north-south road, which I was heading towards. It was so new it wasn’t even on the map yet! They promised perfect tarmac and sparse traffic, and my experience matched their descriptions. Slicing through the beautiful landscape was a great experience. It was also clear why so many of the roads are in such poor condition, with multiple landslides already damaging the surface in several locations.

While cycling this road, a group flagged me down while they were having a picnic on the boot of their car. They offered to share their meal with me, which included bread, chunks of beef, and some kind of fermented yak’s milk that honestly tasted like vomit! The driver then brought out the vodka, and after him and I did a few shots together he got back in the car and drove off!

Next, I set my sights on Song-Köl, a lake at 3000m, known for its stunning beauty, although getting there proved to be a challenge. I had to leave the paved road and navigate a steep track before descending toward the lake along a grassy track.

The lake was truly awe-inspiring. I had heard that during the summer, the shoreline was dotted with yurts for visitors to stay in, but now, only a few shipping containers remained. The isolated feeling up there made the experience even more memorable.

Leaving the lake had me cycling through quite a bit of snow, but this made the scenery even more surreal. That evening I headed down into the valley and camped out with some cows for company.

Since heading up toward Song-Köl, I had been following fresh bike tire tracks on the road. It was always enjoyable to play detective, trying to decipher the direction they were headed and guessing who they might be. On the third day of seeing these trails, I met the French couple responsible, although our encounter lasted only about 10 minutes before we parted ways, each heading in different directions.

Over the past few days, I had realized my deep enjoyment of cycling through the mountains and the feeling of being completely immersed in the wilderness. Consequently, I continued on the mountain roads, relishing the breathtaking views and tackling the challenging road conditions for two more days.

The final mountain road in Kyrgyzstan I was going to conquer was the Tosor Pass. This involved numerous river crossings, leaving me with the perpetual dilemma of whether to ride through, attempt to walk the bike stepping over the stones just above the water, or take the time to remove my shoes and socks and wade through. Most times, I opted to cycle and inevitably ended up with wet feet. I also met Swiss cyclist Maurizio along this road who took some fantastic photos which really show the scale of these mountains.

The last four days had been arduous, taking a toll on my energy, leaving me feeling thoroughly exhausted. Each day, I aimed to conquer a mountain and camp at a lower elevation for a warmer night, which required covering significant distances. On the particular day I made it to Issyk-Kul, a vast salt lake in the northeast of Kyrgyzstan. In the afternoon, I made it to a wild beach along the shoreline, where I took the opportunity to rest, enjoy a swim in the surprisingly warm water, relax on the beach, and build a large fire that night. It was an amazing location and so special to have it all to myself.

Leaving the lake’s shore, I set my course toward the Kazakhstan border, cycling mostly through farmland and steppe for another a day and a half.

Kyrgyzstan has undoubtedly been one of the most best countries I’ve visited so far. The people were incredibly friendly, often offering me food and showing genuine curiosity about my background and travels. Although the cost of food was noticeably higher than in Tajikistan, the country felt far more developed, boasting very good phone signal coverage almost everywhere.

I think I also got very lucky with the weather not having any real cold and experiencing only one afternoon of rain during my entire stay. Additionally, I frequently encountered fellow cyclists almost every day who were all great to have a quick chat to. Finally, the breathtaking landscape and incredible isolation at Song-Köl has probably make it my favourite place of the trip so far.